|

The world of non-commercial film and A-V |

Events Diary | Search | ||

| The Film and Video Institute | | ||||

|

by Edward Ross reviewed by Patrick Tobin |

Last year, I attended the Edinburgh International Film Festival -- the one in Scotland -- and in the lobby of the Filmhouse, the theater acting as central hub, they had a couple little racks set out of this thing called Filmish. I'm a sucker for zines and small press junk, so I veered right toward this Filmish thing, and had myself a flip-through. Now, a year later (and having somehow lost the two issues I bought at EIFF), I'm still amazed at Filmish's genius simplicity. The subtitle says it all: "Comic book essays on film theory." Seriously, how is it that no one came up with this before Scotland's own Edward Ross? And now that he has come up with it, how is it that people aren't aping it left and right?

I have a master's degree in film. Thus, I am qualified to state: 75% of written work concerning film and television is aggravating beyond belief. It's either so full of jargon as to be opaque to non-academics, or it's blather about "dumb fun" (key word: dumb). Even in the case of the best film writing, though, there's a problem with adapting a multimodal audio-visual medium into the linear black-and-white (so to speak) of text. The old saying holds that writing about music is like dancing about architecture; to be honest, writing about art with any visual or audio component has the same problem (even writing about comics.) What each issue of Filmish does is strip-mine what would be a lengthy essay in pure-text format into an easily digested bullet-point format -- but in this compression, we regain the visual aspect that is crucial to film, and which provides a more immediately understandable (if not fuller) context than writing alone can typically achieve.

|

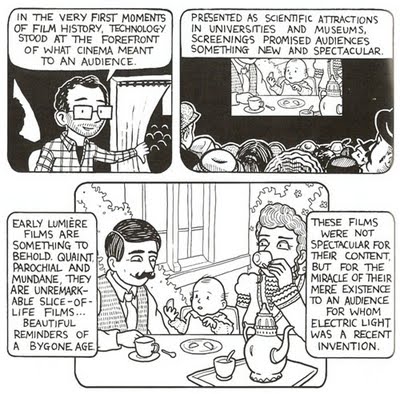

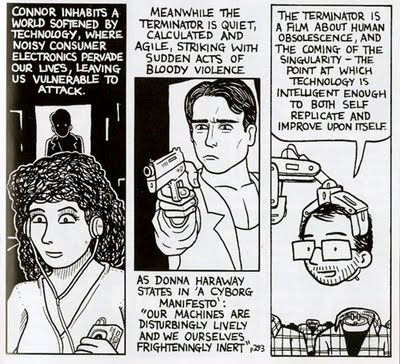

Filmish #3 asks the question (which I am quoting right from page one): "Why does a medium so dependent on technology respond to technological change with narratives flush with mad scientists, rampaging machines, and malevolent AI?" Ross's cartoon avatar, omnipresent as both narrator and star, asks this while done up to look like a Frankenstein, surrounded by robotic menaces including a T-800 endoskeleton, one of Doctor Octopus's tentacles, and Jeff from Scud the Disposable Assassin. He then marches through an abbreviated history of film technology and filmed technology, from the awe audiences gave over to the embryonic films of Lumiere, to Charlie Chaplin's Modern Times, the first film to truly grasp the flipside of modernist industrial culture: the idea that we may have built things we can't beat in a fair race. (This anxiety continues to be expressed in just about any science fiction story with guns involved, though Ross is careful to include early exceptions, namely H.G. Wells's celebration of technocracy, Things to Come.) From there, we walk through the modern and post-modern tendency of films to shudder away from the products of 'technology gone mad,' from nuclear kaiju to David Cronenberg's Videodrome (where television literally destroys the viewers in the most brutal, scatological way possible). Then we sift through a litany of technological sins cinema has demanded penance for: cyborgs (especially Terminators), genetic engineering, time travel. Finally, Ross, closes out the issue with thoughts on cinema's simultaneous rejection and embrace of technology in the real world, with the sudden affordability of professional-quality DIY materials, and the loss of corporate control that came from the explosion of internet-based everything-everywhere culture.

|

Few nerds are single-medium nerds, but most of them only dig deeply into one of their passions. Someone can be a music nerd without understanding acoustic theory, or the role of timbre in electronic dance music. Someone can be a movie nerd and rarely ever stray beyond the multiplex. Someone can be a comics nerd and only follow the X-Men! Filmish exists in one of the spaces between nerddoms, where ideas from different media and disciplines can freely bleed into one another and create something unique. Like I said, I'm shocked that more people aren't ripping Edward Ross off.

Speaking of ripping Edward Ross off, here's a link to his webstore, which last time I ordered something had shipping so cheap I almost felt bad for him. Exploit this while it lasts, true believers.

Patrick Tobin (July 2011).

Patrick holds a Master's in Film Journalism from the University of

Glasgow. He writes about comic books for Multiversity Comics, and his writing

about film is available for birthday parties and bar mitzvahs.

Share your passions.

Share your stories.