|

The world of non-commercial film and A-V |

Events Diary | Search | ||

| The Film and Video Institute | | ||||

The making of Life's Little Gaps

To BIAFF 2008 results | To Making Of Index

Notes on the film | Notes on the production

Emails have been flying across the Atlantic. Scott Hillhouse gave us a fine note on his film, which you can read in Part One. When we asked a few more questions and he realised we really did want to know how such a project was undertaken, he added these notes which are almost a complete beginner's guide to setting up and making such a low-budget production.

I can't begin to tell you how much we appreciate the BIAFF giving us this

opportunity.

The success of our simple short at your festival has humbled us all, beyond

all measure.

The very thought of our work being shown in your beautiful country has placed

an enormous smile on the faces of all those involved. A smile that, I assure

you, will not soon fade.

Budget

Life's Little Gaps was shot with a budget of only $1200 (around £600. )

Don't get me wrong, $1200

is a lot of money to me and most of the cast and crew. It was equivalent

to almost three of my paychecks at the time. Many of my bills had to fall

behind for a short while in order for me to have the money needed to pull

off the production. In fact it took about two months of living off of packaged

noodles and Kool Aid1 to get

me caught back up. So I was well aware of how important it was that I use

every dollar wisely.

Don't get me wrong, $1200

is a lot of money to me and most of the cast and crew. It was equivalent

to almost three of my paychecks at the time. Many of my bills had to fall

behind for a short while in order for me to have the money needed to pull

off the production. In fact it took about two months of living off of packaged

noodles and Kool Aid1 to get

me caught back up. So I was well aware of how important it was that I use

every dollar wisely.

Of the $1200, $550 went to renting a small grip and lighting package2. A local production supply company, understanding I was working with a very limited budget, cut us a really good deal for a four day rental. This package included:

|

(One kilowatt lamp with a lens of several concentric prisms - like a lighthouse.) |

|

(650 watt ditto ) |

|

(450 watt ditto ) |

|

(400 watt ditto ) |

|

("Century" stands - an old brand name - have a tripod base and hinged arms with clamps on which lights and other gear can be held in place.) |

|

(Flags are panels of material which block and direct light. Solid ones block light and silk ones diffuse it.) |

|

|

|

|

|

(extension electricity cables) |

|

(A clamp which fastens to a pole or wooden beam and has a second set of jaws to hold a lamp or other piece of kit. The Mafer clamp was used to clamp a light to a 2x4 wooden plank in both the closet and the bathroom scenes.) |

Other equipment used was a wheel chair (the poor man's dolly), a few China balls, and a couple fluorescent lights I picked up at a local department store. The China balls are pleated paper spheres which can be purchased for around $20 if you go to an oriental market place like I did. If you try to purchase them from a film production supply company, the price goes up dramatically. [Editor's note - they can be used with high-powered lamps to get light into a scene so long as they are constantly watched because there is a high risk of them catching fire.]

Another $400 went to feeding all the cast and crew. I once read that something like 90% of all prison riots start because of the food, or lack thereof. From my short time in the industry, I've found that to also be the case on film sets. So I've learned that if you keep their stomachs happy, their spirits will often follow suit. For the four day shoot, I spent $100 a day. Half of that would be for lunch and the other half on snacks and bottled water for the Kraft Service3 table. I would say that if it hadn't been for the brutal heat and exercise, the cast and crew might have put on a couple of pounds during production.

A total of $200 went for supplies like lumber, screws, paint and other materials needed to build some of the set pieces. Particularly, the wild walls [false removable walls] and a portion of the door that had to be constructed for one of the film's sequences.

The remaining $50 went for supplies to make the scripts, sides [daily script pages], and other paperwork needed for the production. Little things like paper and ink cartridges can't be forgotten when doing your budget.

Since the film's completion, I have spent an unimaginable amount on blank DVDs, cases, jackets, inserts, and of course, festival entry fees. All of which is done for the sole purpose of getting our short story to as many viewers as possible. So far, I feel as a producer, I've gotten every dollar's worth, and then some.

Pre-Production

With a little more than

six months of pre-production, I was better able to prepare myself for the

production nightmares that often present themselves on set. A couple of the

tools I used were storyboards, digital stills, and camera plots. Though,

I wasn't able to get a storyboard done for all 132 shots, I did make sure

we had a camera plot for every shot in the film. Notwithstanding those shots

we came up with on the fly. These do occur and I am a firm believer in the

fact that a production should never be a slave to the script or the shot

list. Sometimes the most beautiful shots will present themselves on the day

of shooting.

With a little more than

six months of pre-production, I was better able to prepare myself for the

production nightmares that often present themselves on set. A couple of the

tools I used were storyboards, digital stills, and camera plots. Though,

I wasn't able to get a storyboard done for all 132 shots, I did make sure

we had a camera plot for every shot in the film. Notwithstanding those shots

we came up with on the fly. These do occur and I am a firm believer in the

fact that a production should never be a slave to the script or the shot

list. Sometimes the most beautiful shots will present themselves on the day

of shooting.

Camera Plot

The Camera Plot, for us anyway, was just an overhead floor plan of our location, depicting the position of the camera and the actor's marks. As I am working with the actors, the 1st Assistant Director simply hands the cameraman the next plot and he goes right to where he needs to be and sets up. This alone saved us an abundance of time once we started shooting.

Digital Stills

Another step I took was to take a few digital stills of one of my friends acting out certain scenes so I could work out my framing and composition. Not to mention, it gave me a good idea of how I might want to light the scene as well. It's amazing how something like taking digital stills can allow you to work out problems beforehand that usually only present themselves during production.

Storyboard

As a grip working on a shoot in Los Angeles, I had the honour of working

with a very talented French director, whom I had a personal conversation

with following his shoot. In our discussion of how things went, I explained

to him that I hadn't noticed any storyboards on the shoot. He replied "I

believe storyboards limit my vision." Not wanting to upset him, I just

said OK. Noticing the odd look of confusion on my face, he then asked me,

"Do you disagree?" To which I replied,

"Yes, but I do understand why you feel that way. Me, personally, I believe

storyboards define your vision." He later admitted that they can be useful,

but that he wasn't very good at drawing.

I hear that a lot among my fellow filmmakers and my reply is always the same. You don't have to be a Rembrandt to get across what you want in the frame. Stick people will do the job just fine, and with all the software available today, the ability to draw isn't even needed. If you can't afford the software or just don't want to be embarrassed by your awkward stick figures, then pick up the cheapest digital camera you can find, get a few friends together, and block out your shots that way.

The point I'm trying to make is that if you walk on to your set with a detailed shot list, storyboards, and/or camera plots, your cast and crew will see the amount of effort you have already put into the project and will often try to match it with their own performance.

In film school, one of the most common questions was "What could Production Company X have done to avoid the mistakes encountered during production?" I learned that the one fail-safe answer was always "more pre-production." Six months may sound like a lot but I assure you I wish I had taken twelve. If you were to ask me which stage of production is most important, my answer is always pre-production. Whatever problems you don't work out there, will come back to haunt you once you are on set.

Set Construction

Because the script called

for our two main leads to spend part of the evening in a closet, we were

well aware that trying to fit two actors, a cameraman, and a boom operator

into such a small place would be near impossible. (You should have seen us

in the restroom, all piled into the bathtub like a bunch of sardines.) So

we decided to cut the main room in two, by using "wild walls" to construct

our own closet. Whenever you see a shot in the closet there is always one

of the four walls removed.

Because the script called

for our two main leads to spend part of the evening in a closet, we were

well aware that trying to fit two actors, a cameraman, and a boom operator

into such a small place would be near impossible. (You should have seen us

in the restroom, all piled into the bathtub like a bunch of sardines.) So

we decided to cut the main room in two, by using "wild walls" to construct

our own closet. Whenever you see a shot in the closet there is always one

of the four walls removed.

Wild walls

Wild walls are sections of wall that can be quickly moved to accommodate your shots. The main room had eight foot ceilings and was roughly twelve feet across so the walls were built in four foot by eight foot sections. Each section of wall, with the exception of the one holding the closet door was built with 2x4s and a 1/8 inch sheet of particle board which we refer to as skins. These skins are relatively cheap and are much lighter and easier to move than drywall [plasterboard]. Once painted, you can hardly notice the difference.

Another situation that

had to be planned out in advance was the brick coming through the window.

There aren't too many people who will let you chuck a brick through their

front door window, so we had to construct our own. In film school they drill

in your head the fact that when building a set piece, only build what you

will see in the frame. So we only constructed about a three foot section

of the door. Then we attached a skin perpendicular to the door to give the

impression that we are looking at where the two walls meet.

Another situation that

had to be planned out in advance was the brick coming through the window.

There aren't too many people who will let you chuck a brick through their

front door window, so we had to construct our own. In film school they drill

in your head the fact that when building a set piece, only build what you

will see in the frame. So we only constructed about a three foot section

of the door. Then we attached a skin perpendicular to the door to give the

impression that we are looking at where the two walls meet.

If I was to remove the mask (black bars at top and bottom) from the shot, you would probably see me standing behind it holding a brick. In the bottom of the frame, just a couple inches below the door knob, you would see the pavement of one of our crew member's patio. At a local department store, I purchased a small piece of cloth material that resembled the curtains used during principle photography, and was able to borrow an old door knob and lock. Our door piece was constructed so that I could slide a new piece of glass in for each take. We purchased three sheets, costing us around $20, but ended up only using one. I was so impressed by the first take that I didn't see a need for a second. Life is rarely so kind.

Location and Props

We had lost our original location early in pre-production due to circumstances beyond our control. Sadly, I had already started storyboarding and plotting out my shots and the script called for a very specific living area. This made it all the more difficult to find a replacement for our location, but once again, luck was on our side. A young member of the Oklahoma Movie Makers came forward and offered us the use of a family owned house that just happened to be vacant. To my surprise the house was almost identical. The only major difference was the absence of a room directly across from where the characters sleep. So now all we had to do was construct a couple more wild walls to close off one side of the room and we were in business.

Though the family that allowed us the use of the property didn't charge us, I did however reimburse them for their electric bill. I felt it was the least we could do for them showing us such hospitality. One of the many running themes in the story was that our main characters live a modest lifestyle. Though they are rich with emotion and love for one another, their home should convey a family with very little monetary assets. This made collecting props and set dressing all that much easier to find. People are more likely to loan you a broken down old lamp, or a worn out twin bed, as apposed to a pair of Tiffany cuff links, and a Ming Vase.

All the art you see hanging on the walls of their home, with the exception of one, was done by a very talented local artist named Jay Botello. He even did the ones that were supposed to have been done by our main character and are hanging next to his bed. He was also the one who provided us with the location. The one exception was a painting of mine hanging above the TV that ironically never made it into a shot. The crickets on our lead's pajamas were also designed by Jay, and were ironed on the day before the shoot by my 1st AD and me. We only had a couple sheets of iron-on transfers so if you look closely, you'll notice the top portion is covered in crickets, but the pants only show a few. The t-shirt worn by the other character is an ad for a beer label I designed in film school and was ironed on the same way.

Most of the remaining props, including the dirty clothes scattered about the floor, were pulled from my own collection. Yes, I did wash them before I asked the actors to role around on top of them. What I wasn't able to provide, other members of the cast and crew were quick to contribute. It's amazing what a group of motivated individuals can come up with on such short notice.

Production

This is the moment we all live for, when we see the lights fire up, the camera starts rolling, and there before our own eyes, our characters come to life. Some call it the rush of a lifetime, and I would never argue that point. It's hard to believe that once production is finished, a depression sets in for a lot of the cast and crew. Ironically, we miss the rushing around, the stress levels, and the cheap food that are only present during the shoot. There is something to be said about the cohesion of the cast and crew during production. It's almost as if you become a family and when wrap is called we hate to see it end.

We shot the majority of the principal photography on location in only four days. We shot it over two weekends during the late summer of 2005. We did our blocking [marking where actors and kit will go] on a Thursday and went right into shooting the next evening. We only shot on Friday and Saturday nights due to the fact that just about every one of us had full-time jobs, and since the entire story took place at night, it would be the only time we could shoot.

Having worked on a few professional sets in Los Angeles, I was used to working no less than twelve hours a day. I knew, however, that I would not be able to ask that of this particular cast and crew, at least not for all four days. So I warned them in advance that the days would grow longer as we went, and the final day would definitely be the longest.

The first day we were able to start a little early because the first shots were the bathroom shots and the bathroom had no windows. So the shoot lasted about eight or nine hours. The second night we drew it out a bit and I was able to get twelve good hours of shooting. The following weekend, I slowed the pace down a bit and we only put in about ten hours, but on the last day we ran almost sixteen hours to complete all the shots. We pulled off our last shot as the sun was coming up. We were all worn out and tired, but we knew we had done something great.

A couple months later we would pick up the shots of the crickets, the brick through the window, and one other shot I really wanted. Each of these only took a few hours and they are what I refer to as 2nd and 3rd unit production. These shots only required a handful of crew members and none of the actors.

Transitions / Lighting

Transition: the process of taking me from one shot to the next. Though my translation is crude and the meaning quite simple, the time spent designing good transitions could make all the difference in your film. Sometimes a bad cut can pull the audience right out of the story but a good one will accent or heighten the emotion you are trying to convey.

A good way to look at this is to regard the camera as simply an extension of your eye. If someone steps in front of you and blocks your view, you move so that your view is no longer obstructed. This gives you the perfect motivation to move the camera. This is where I use the "Body wipe".

The body wipe is simply a term I use to describe when I shoot one shot ending with an object or person walking through the frame then shoot the next scene starting with the same effect. I then cut the shots together at the precise moment the object or person is covering the entire frame. If the cut still looks rough, a small dissolve can often smooth it out a little more.

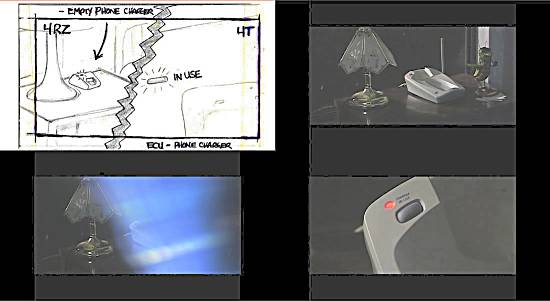

An example of this is

when the burglar notices the phone charger light is on. I needed to show

the light reading "IN USE" on my next shot and since it was an Extreme Close-Up,

we weren't able to fit the burglar in between the camera and the phone. So

we took the blue plaid shirt he was wearing, and wiped it in and out of frame.

This gave us a smooth transition that hopefully keep the audience involved

and heightened the overall feeling we were trying to convey.

An example of this is

when the burglar notices the phone charger light is on. I needed to show

the light reading "IN USE" on my next shot and since it was an Extreme Close-Up,

we weren't able to fit the burglar in between the camera and the phone. So

we took the blue plaid shirt he was wearing, and wiped it in and out of frame.

This gave us a smooth transition that hopefully keep the audience involved

and heightened the overall feeling we were trying to convey.

As for lighting, I tried to follow the advice of another independent filmmaker who was featured in an article of a poplar cinematography magazine I read. He said the secret to his film's look was he lit his set once and worked in all his shots from the existing light. That is exactly what I tried to do. Once we set the lights we basically used bounce cards to shift the light where we needed it. This helps the shots match and keeps you from doing a lot of colour correction in post [production].

Post-Production

I had told myself that I was going to take a short break before I started editing the footage.

Well the break lasted about one night's sleep. I was too anxious to just sit on the footage. I had to start cutting.

Most of the software I use is made by Adobe. Many could claim that there is better software available and again I would not argue that point. It's just the fact that I am familiar with their products and as my father always said, "Dance with the lady that brought you." In other words, if it has worked for you this far, stick with it.

By the time I put out the final output, my old computer couldn't have handled one more cut. I had so many cuts, colour corrections, noise reductions and sound effects that just to open the file took about five minutes. Though I could have spent another six months tweaking the film, my poor computer couldn't take anymore. I suppose that was a good thing because like a typical artist, I would have never felt it was truly complete. Still to this day I wish I could go back and remove some hiss in some parts, or knock down some of the pinks on some of the flesh tones. That's when you have to listen to that little voice in your head that's telling you to walk away and leave it for the audience to decide.

Though I have no children, I would have to imagine a film being a lot like a child growing up. Before too long it's time for him to go out into the world on his own, and all you can do is hope that you gave him everything he needs to make it. While he is gone, you sit and ponder all the things you wish you would have done better.

Directing

Napoleon once said that there are two ways to lead men, either by interest or by intimidation. With the latter you always run the risk of running into that one person who is bigger and meaner than you, and there is always someone out there who fits those shoes. Myself, I choose the first. I have seen what the human spirit can accomplish and it is a powerful force. Motivation is a contagion, and as director, you have to walk on that set with the disease evident in you.

One of my favorite mottos is, "leadership by example". Though it is a simple thought, it is, in my eyes, the secret to being a good leader. I have found that if you are willing to buckle down and work your hardest, others will follow suit. When it comes to independent filmmaking, leadership is earned, not appointed. Sure they will work because they have to, but their proficiency cannot match that of someone who is excited about their work. Motivation is a fire, and if it is evident in you, others will see this and feed from it.

Each member of the cast and crew was present every day of shooting, and though the conditions were harsh and sometimes unbearable, they each performed better than I could have ever imagined. I really believe I couldn't have gotten a better crew if I would have paid them. These are men and women to whom I owe everything and will spend the rest of my life repaying. If I am ever asked, "what is the secret of your success", I will always reply, "I surround myself with people much better than myself."

The Cast and Crew

Details of who did what are on

www.lifeslittlegaps.com but

the team were in alphabetical order:

|

|

|

- House (aka Scott Hillhouse )

Go to Notes on the film

| 1 | Kool Aid is flavoured drink powder. It is a trade mark of Kraft Foods but the name is commonly used for similar products from other companies. |

| 2 | Grips are the people on a film set who handle lighting and rigging equipment, including camera dollies, stands and so on. The work closely with the cinematographer and chief electrician. A grip and lighting package is a collection of equipment grips might need. |

| 3 | Kraft/Craft Service - part of a film crew which supports all the others. On big sets they act as guards, protect sets and crucially provide a drinks and snacks service for the crew. |

Share your passions.

Share your stories.